October 20, 2025

'Brilliant Minds' – Zachary Quinto stars in a medical drama with empathy and wonder

Laura Moreno READ TIME: 1 MIN.

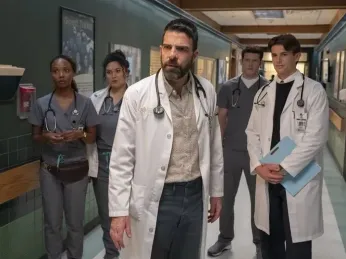

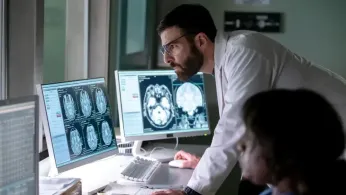

In a crowded field of medical dramas, “Brilliant Minds” stands out. Currently in its second season on NBC and streaming on Peacock, it features Dr. Oliver Wolf, a brilliant neurologist whose unorthodox methods probe the frontiers of brain science. The series is written and created by Michael Grassi.

The show is inspired by Dr. Oliver Sacks, the late openly gay Oxford-educated neurologist and author of books like “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” (1985). Sacks was a trailblazer in destigmatizing and humanizing neurological brain disorders. Very aware that each patient is different with a unique configuration of health and life challenges, he firmly believed in “listening” as the ultimate cure.

Sacks’ quiet rebellion against strict protocols that leave no room for ingenious doctors to actually solve unique problems is a throwback to a time not so long ago when brilliant caring doctors had room to achieve miraculous results against the odds.

But today medicine is increasingly like an assembly line. Medical protocols were massively re-written in 2004 apparently with money, not good health, in mind. The result has been a mass exodus of doctors leaving the medical profession, or refusing to accept medical insurance and its dictates as payment.

“Brilliant Minds” is a subtle acknowledgement that the current state of medicine, particularly the field of psychiatry, leaves much to be desired. Its failures are clear in light of its outcomes, seemingly exploiting society’s problems rather than mitigating them.

What elevates “Brilliant Minds” beyond the competition is its steadfast endeavor to unravel and solve the enigma of mental health as a central theme. Dr. Wolf at times breaks protocol to treat the whole person out of genuine caring.

Grassi has called the show a torch passed forward, adapting Sacks’ insights to today’s exponentially increasing mental health crises, much of it no doubt a result of instability on the world stage, events like mass shootings, and witnessing new war crimes being committed week by week.

Queer resilience

Notably, the fictional Dr. Wolf and the actor Zachary Quinto, like Dr. Sacks, are also openly gay. It’s a thread Grassi weaves subtly, celebrating queer resilience in medicine’s macho maze.

Quinto decided to come out as gay in a New York Magazine article, and blogged, “When I found out that Jamey Rodemeyer killed himself I felt deeply troubled. But when I found out that Jamey Rodemeyer had made an ‘It Gets Better’ video only months before taking his own life, I felt indescribable despair. I also made an it gets better video last year in the wake of the senseless and tragic gay teen suicides that were sweeping the nation at the time. But in light of Jamey’s death, it became clear to me in an instant that living a gay life without publicly acknowledging it, is simply not enough to make any significant contribution to the immense work that lies ahead on the road to complete equality.”

Zachary Quinto is perfect for the role and delivers an outstanding performance, but he is an ironic choice to play a brain neurologist, given that Quinto previously played a serial killer obsessed with his victims’ brains on NBC’s “Heroes.”

In addition, the supporting roles of the interns pulse with authenticity as ambition clashes with idealism, and interns grapple with burnout and bias, mirroring the very disorders they treat. Devoid of the stoicism that often characterizes hospital tales, the show unabashedly reminds us that healers harbor hidden fractures, too.

The interpersonal tensions feel organic and real as Alex MacNicoll, Aury Krebs, Spence Moore II, and Ashleigh LaThrop deliver solid performances.

Furthermore, “Brilliant Minds” is a new type of show that perhaps most resembles “The Good Doctor” with its neurodivergent savant Dr. Shaun Murphy, but with amped up storylines. Where “House, M.D.” dealt with cynical puzzles and Dr. Gregory House’s addiction to pain prescriptions, this show leans empathetic with less snark and more wonder. Quinto’s character even gets a bit of a romance in the second season.

“Brilliant Minds” undoubtedly appeals to thoughtful fans of “Grey’s Anatomy” interested in looking beyond typical face-value diagnoses to try to understand and heal the complex puzzles of the human mind.

Perhaps the best thing about “Brilliant Minds” is its genuine empathy for patients in a genre that at times feels like it’s on autopilot. Quinto’s nuanced lead, paired with Grassi's wisdom-infused scripts drawn Sacks’ work, transforms a medical drama into a revelation.

https://www.nbc.com/brilliant-minds