Sep 21

Kink ink! – Folsom-themed books about leathermen, lesbian vampires, and a how-to instructional

Jim Piechota READ TIME: 1 MIN.

Welcome to Folsom Week here in San Francisco, where the scenery is as stunning as the city’s hidden underbelly---and just as ripe for appreciation. Leather Week is an opportunity for experimentation, exploration and boundary pushing, and a time when the atmosphere in leather bars and street fairs is heightened to a devilishly carnal level.

We present a collection of newly published books on kink, leather, BDSM, and, well, horny Bay Area vampires at sea on a cruise, and why not? Let these works of art whet your appetite for the darker side of sexuality, the temptations of control and submission, and even possibly as primers to all the gatherings and play parties planned for this season of dark adventure and pleasure.

“Leather Forever” by Pete Fitz, $17.99 (Self)

The Dom/sub, Daddy/boy interpersonal dynamic is explored with brio and impeccable detail in Pete Fitz’s debut novel. In Los Angeles, Jesse Reed is a chiropractor who yearns to make a lasting connection with another man, preferably a man who is at ease asserting his dominant side. He meets Grant Morgan, whose swagger, flirtatiousness, and penetrating gaze ignite the submissive yearnings in Jesse and a hot and heavy relationship is born.

But that union comes with both benefits and complications, among them Jesse’s somewhat reckless surrender to Grant’s tutelage of the ways and means of leather culture. Under Grant’s careful watch, however, Jesse’s innocent curiosity morphs into a full-blown dedication to BDSM and the southern California and New York leather communities, including active participation in leather contests.

Author Fitz draws from his experiences as a contestant in the 2001 Mr. LA Leather competition to depict the kinds of emotions and motivations that these events evoke. The result is an authentic, immersive portrayal of the messy politics, the determination, the ego-driven melodrama, and all the hot sex, jealousy, celebration, and power dynamics swirling around queer leather contests across the globe.

Heavily (and respectfully) exploring themes of identity, control, submission, and sexual and emotional domination and submission, Pete Fitz has penned a highly entertaining, provocative novel that puts sex, BDSM, and the dynamic queer leather community front and center.

www.instagram.com/petefitzwrites

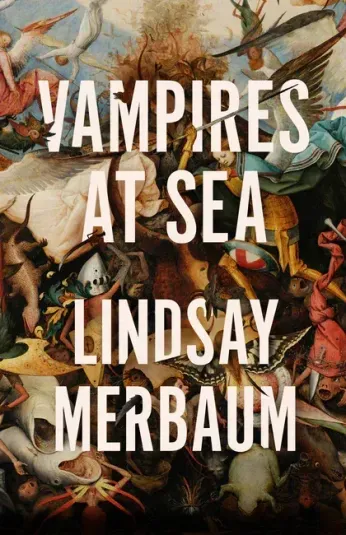

“Vampires At Sea” by Lindsay Merbaum, $18 (Creature Publishing)

The title of queer author Lindsay Merbaum’s new erotic horror novella tells it all: there is a pair of sarcastic ageless vampires at sea on an enormous cruise ship, and no one is safe from their kinky erotic desires. San Francisco vampires Rebekah and Hugh receive a tempting travel flyer in the mail, and they immediately leave their cramped Cole Valley apartment to set sail across the Black Sea on the Zorya, a “discount cruise for classy art queers.”

Once aboard, Rebekah regrets her decision to board the ship, which she calls “a big wet dumpling of lust,” especially after witnessing the hordes of passengers scrambling for the greasy steamy buffets and partaking in the “rainbow waterslides powered by the passengers’ own poop.” But both vamps stick around: Rebekah feeds not on blood, but on sexual emotions, while Hugh gets high from human anxiety and despair.

There are orgies galore, as well as exotic ports of call where the thirsty duo drink their fill of good and bad emotions. It’s a wild ride courtesy of Creature Publishing, a literary group who consider themselves a purveyor of “feminist horror…founded on a passion for feminist discourse and horror’s potential for social commentary and catharsis.”

Merbaum’s second novel (after 2021’s superb, parallel world-builder “The Gold Persimmon”) is a story that’s sexy, engrossing, hilarious, snarky, nasty, and supremely smutty in the best way possible. This is a perverted pleasure indeed.

www.creaturehorror.com/books

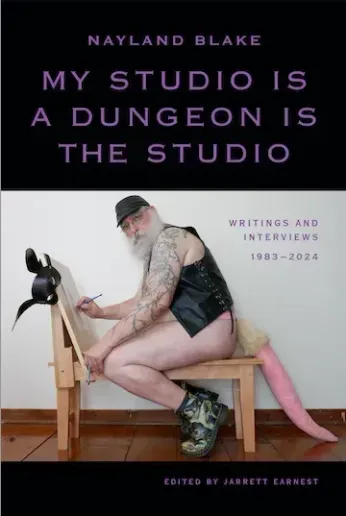

“My Studio is a Dungeon is the Studio” by Nayland Blake, $28.95 (Duke Univ. Press)

Distinctively talented American artist and curator Nayland Blake has collected their writings (many previously unpublished), scripted performances, collages, and interviews from the early 1980s to the present in this provocative display of art, bondage, and sexual and gender liberation.

Chapters range from Nayland’s distinct appreciation for the artwork of “authentic icon” and sensualist Tom of Finland, interviews with various artists, and, of course, opinions on the world of conceptual art, sexuality, queer uniqueness and authenticity. This gem of a quote nicely sums up their thoughts on being defiant and independent with one’s art: “If there’s one gift I would give to artists, it is this: Don’t wait, don’t wait to find career security and then come out with your weirdness. Come out at the start because it doesn’t get any easier.”

Visually stunning and gloriously boundary-pushing, Blake’s art also explores their queer sexual life and affinity for BDSM through ‘zines, a catalog of porn reviews they’ve written for this very newspaper, their early connection with The Addams Family dynamics, and pages of kink-appreciative musings like an essay on the “Basics of Psychological Status Play.” This unconventionally artistic anthology of work is not to be missed.

www.dukeupress.edu

“Kink for Dummies” by Jaime M. Grant & Jack Harrison-Quintana, $24.99 (Wiley)

Always been curious about how you might fit into the darkly tempting, titillating world of alternative sexy time? Then look no further than this new educational and instructional guide to all things kink by queer sex activist and researcher Jaime Grant and queer Latino activist and author Jack Harrison-Quintana.

In this guidebook, readers will learn step-by-step advice and guidance on communication strategies to get the most out of scenes and playtime, fundamental kinky protocols, the “tools” of the trade for certain styles of kink behaviors. Perhaps the most important section of the book addresses strategies for overcoming shyness and personal sexual reticence in order to embrace the inner bold, brassy, and brazen kinkster within you. Applying these techniques, the authors promise, will allow one to ask (and receive) the pleasures of kinky play of any kind.

This particular “Dummies” volume in the exhaustive library of guidebooks makes for particularly assistive, assertive, and deliciously offbeat sexual self-help for everyone from the most vanilla to the aggressive Dom BDSM master in the bedroom and beyond. In these trying times, it’s important to stay curious, folks, and this book is the perfect shame-free place to start exploring your kink nature, initiate kink in the bedroom with partners, and to fully embrace and proactively partake in the wonderful delights the kinky world has to offer.

www.wiley.com