May 3, 2013

Game Changer: Sports' Shifting Attitudes Toward LGBTs

Lana Cooper READ TIME: 11 MIN.

NBA center Jason Collins recently made headlines and history when he became the first openly gay athlete currently playing for one of sports' Big Four professional leagues. While Collins' declaration is undoubtedly a game changer, several athletes and organizations, both past and present, have contributed significantly to an increased presence of LGBTs in professional, semi-professional and amateur sports.

On May 31, New Jersey-based Minor League Baseball team, the Lakewood Blue Claws, will host an LGBT Night at Energy Park. The Blue Claws, who are affiliated with Major League Baseball's Philadelphia Phillies, join the ranks of countless minor and major league sports organizations that sponsor an LGBT Night. These themed events, which also include Irish Heritage Night and Faith Night, are designed to attract and welcome fans from a wide arc of backgrounds to live sporting events.

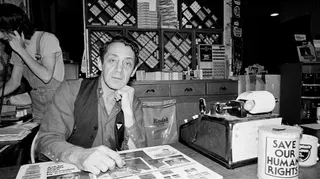

Cyd Zeigler, Jr., award-winning journalist and co-founder of Outsports.com, spoke candidly to EDGE and noted that "teams with these nights are not interested in making a big political statement, but there could be an occasional executive who does have that in the back of his mind. Baseball has 81 home games every year that they have to sell out during the course of the season. Gay Night or LGBT Night just happens to be one of those ways that they make money. In a lot of ways, that's great that we're treated, in the eyes of major league baseball, like every other niche group."

Skeptics may attribute sports' push to be more inclusive of LGBT persons to "pink money," a slang term that refers to the purchasing power of the gay community. A 2011 article in the Philadelphia Business Journal predicted that disposable income held by LGBT individuals would exceed $835 billion.

Zeigler put the theory to rest, saying that everyone's money is green.

"Sports teams don't care if it's pink dollars, purple dollars, yellow dollars, or red dollars," said Zeigler. "They just want the dollars."

Zeigler, who has collaborated with MLB's New York Mets and the NBA's Los Angeles Clippers to produce several LGBT Nights, mentioned that "some teams will go the extra mile because they do recognize that there is some importance behind this particular night given the state of homophobia in sports."

NBA’s Jason Collins Gives a Voice to Gays in Sports

The issue of homophobia in sports reached an uncomfortable boiling point earlier this year when cornerback Chris Culliver of the San Francisco 49ers made homophobic remarks in an interview with Artie Lange.

"No, we don't got no gay people on the team. They gotta get up out of here if they do. Can't be with that sweet stuff," said Culliver. When prodded further, Culliver intimated that that, even hypothetically, he could not share a locker room with a gay teammate, saying, "You gotta come out ten years later."

Culliver later apologized for his remarks, but that rarely spoken sentiment likely contributed to why it has taken so long for a professional sports team to have its first, active, openly gay male athlete emerge.

That changed on Apr. 29 when seven-foot tall, 34-year-old NBA center Jason Collins gave a face and a voice to others who want to "just try to live an honest and genuine life."

Collins' announcement, which came in the form of a Sports Illustrated article he co-authored with writer Franz Lidz, by no means diminishes the courage and contributions of athletes like former professional tennis player Martina Navratilova or the WNBA's first overall 2013 draft pick, Brittney Griner.

As perhaps the most high-profile, currently-active lesbian athlete of her generation, Griner shares the spotlight with other openly-gay female athletes including professional soccer players/philanthropists Joanne Lohman and Lianne Sanderson, as well as MMA fighter Liz Carmouche -- all of whom were named to the Advocate's Top 40 Under 40 list of public LGBT figures.

Yet, until now, a double standard seemed to exist for lesbian athletes as opposed to openly gay male sports figures.

"Women are simply more willing to share their emotions and personal life than men are, but I also think that money makes a huge difference," said Zeigler, who noted that when comparing the salaries of female professional athletes to those of their male counterparts, women make considerably less. The average salary for a WNBA player in 2012 was $72,000, which stands in stark contrast to the $5.15 million average for an NBA player.

"When you're making a quarter-million dollars a year playing your sport, it's a lot easier to make life decisions separate from money than when you're making $20 million a year," said Zeigler. "The amount of money put at risk goes up for men because male athletes are simply making more money."

Although they hail from different ends of the sports spectrum and are divided by several decades, both Navratilova and Griner chose to declare their sexual orientation while active in their careers.

Prior to Jason Collins' announcement, the decision for male athletes to come out was typically delayed until after that athlete had retired from professional sports. Former NBA basketball center John Amaechi and former NFL players Esera Tualolo, Don Kopay, and Wade Davis all came out after their respective retirements.

Out Athlete Wade Davis Founds LGBT Youth Sports Camp

In 2003, Wade Davis' NFL career was cut short due to a leg injury. Since then, Davis has become an author and activist who has sat on the board of the New York Gay Football League, the sports advisory board of the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) and the You Can Play Project, which recently teamed with the National Hockey League "to make the NHL the most inclusive professional sports league in the world."

Davis spoke to EDGE about his latest project, the YOU Belong Initiative, a three-day sports camp that will be held in Chicago on July 25-28. Open to LGBTQA youth between the ages of 14-24, the program will grant participants access to NBA and WNBA athletes who will help them hone their skills on the basketball court. YOU Belong will also include workshops on a variety of topics including anti-bullying, HIV/AIDS education and youth leadership development.

Davis hopes that the program will demonstrate how an LGBT youth "can lead not just as an athlete, but also as a better human being."

Currently, YOU Belong is working with local GSAs nationwide to get applications into the hands of young people. Davis plans to offer the program once every three or four months, moving it around the country and focusing on a different sport each time. He is optimistic that YOU Belong can attract more sponsors that will allow him to hold the camp once every two months as opposed to once per quarter, as well as offer it free to young athletes.

Although the program's initial offering revolves around basketball, future YOU Belong camps will be devoted to soccer, softball and baseball -- sports chosen specifically for their accessibility to all youths and that allow women to play, as well.

"That's where the name YOU Belong comes from," said Davis. "Oftentimes, queer kids don't feel that they belong in sports. I always felt that I belonged in sports because I fell in love with the game before I knew I was gay. But there are kids who know they are gay first and may say to themselves, 'I don't feel like I belong here.' What we want to create is an environment where young people feel that they belong in any sport or any industry. And I also feel that it's very important to have straight people and allies there, as well, so that an amazing, educational process can happen for all who are involved."

The YOU Belong initiative is very much informed by Davis' personal experiences in professional sports and his own decision to come out.

"When you live in the closet and you're inside your own head day after day, it's exhausting and you start to believe that who you are is wrong and that you're not worthy of anyone loving you," he said.

Davis explained that he was tired of not being able to express who he was, but fortunately, was able to surround himself "with people who loved me and cared for me regardless of my sexuality, who said that 'who you are is enough.'"

"I've been trying to reframe the whole idea of coming out because it's not so much a coming out process as it is inviting people in," said Davis. "I'm actually inviting people into my life and to understand me in a different way -- finding people who make me feel comfortable enough to invite them into my personal life. When I started to do that, I was able to start loving myself."

While Davis is using his position of prominence to instill a sense of self-worth and valuable life skills in young LGBTQA athletes across the nation; the Greater Philadelphia Flag Football League (GPFFL) is fostering good will in its own backyard.

Philadelphia Brings Together 40 Gay Flag Football Teams

As an official member of the National Gay Flag Football League (NGFFL), the GPFFL was instrumental in the City of Brotherly Love being chosen to host the 14th Annual Gay Bowl in Oct. 2014. The event will bring together 40 NGFFL teams and over 600 athletes from around the country to Philadelphia's Fairmount Park to compete.

The GPFFL has come a long way in a short span of time. What began in 2009 as a pick-up league without referees has now morphed into the fastest-growing recreational LGBT sports league in Philadelphia.

"We offer a safe haven and athletic outlet for people who aren't necessarily the greatest of athletes but who are interested in having fun and being part of a community," acknowledged GPFFL Commissioner Justin Dolci. "What I love is that we do a lot of philanthropy. It's been a hallmark of our league since it started."

The GPFFL was one of the first sports organizations to produce an It Gets Better video (see below) offering encouragement to LGBT youth. As of last year, they became an official 501(c)(3) non-profit and have raised over $10,000 this year alone, and $50K since the league began, for a number of local charitable organizations including the Manna hunger relief program. In 2012, the GPFFL was nominated for the Delaware Valley Legacy Fund's Hero Award, which recognizes philanthropic efforts by individuals and organizations within the LGBT community.

Beyond the GPFFL's philanthropic works, first and foremost, the league exists as a group of LGBT persons and straight allies who play throughout the spring and fall and who are supportive of one another year round.

This year, the GPFFL counts three transgender persons among its numbers. As one of these players was transitioning, GPFFL members threw a party/fundraiser to help pay for their teammate's gender reassignment surgery.

"Our league is a non-stop supportive community that revolves around not just football, but life," said Dolci, who has been with the GPFFL almost since its inception. "It's about being able to support each other because we understand that we come from all different backgrounds."

Despite these different backgrounds, there is a common thread to the stories told by both professional and amateur LGBT athletes. Like Wade Davis, Dolci also played sports in high school and dealt with similar feelings of exclusion.

"I started off playing three sports as a freshman in high school. By the time I got to my senior year, probably around the time that I started to realize I was gay, I wasn't playing any sports because I felt so secluded. I felt like I was hiding," said Dolci.

Although Dolci came out more than 15 years ago, like Davis he credits the importance of straight allies in the fight for equality and how essential their support is to the cause. While the NFL can look to recently-retired Scott Fujita, a linebacker for the Kansas City Chiefs and straight player who has been vocal in his support of gay rights, Dolci is overwhelmed by the everyday allies who participate in the GPFFL, saying, "We cannot stress enough the amount of collaboration from our straight allies who are supportive and say, 'We've got your back. We love you and we support you.'"

For every Chris Culliver, there is a positive melting pot of personalities throughout the LGBTQA community of sports fans that have helped to create an environment where an athlete on the level of Jason Collins finally felt comfortable enough to come out.

"The fact that there is a majority of people who are so supportive of Jason Collins indicates that, in two or three years from now, this wave of support will be the norm," said Dolci. "Coming out won't be an issue -- or at least it will be less of an issue. We're breaking down barriers."